Showing Hospitality to the Stranger (and the One with Strange Ideas)

by Stuart Pickell, MD, MDIV, TCMS President

This article was originally published in the July/August issue of the Tarrant County Physician.

MANY MAJOR RELIGIONS ENCOURAGE adherents to break down barriers between people. The Abrahamic tradition, which includes Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, commends the practice of hospitality, of removing barriers and welcoming the stranger as a guest. The Buddhist tradition takes it a step further, teaching that our connections are real and our divisions are not, so that the very distinction between one group and another- between insider and outsider- is an illusion.

Hospitality is the art of creating community. It is an act- a choice- of welcoming the stranger as a friend, choosing amity over enmity. But encountering the stranger can engender uncertainty. We must decide if the stranger will remain a foreigner whom we keep at a safe distance or become a guest whom we welcome in. Put another way, will we demonstrate hostility or hospitality?

Hostility and hospitality, quite different in meaning, derive from the same reconstructed Proto-Indo-European noun ghóstis, which highlights the ambiguity we experience and the choice we must make. The stranger- or even a strange idea- challenges us. The stranger can be a guest or an enemy but not both at once. The stranger’s presence forces upon us a decision that will require us to examine and assess our relationship to the stranger. As a rule, communities are strengthened when they successfully create room for the stranger to feel welcomed.

On a national level, our ability to find common ground amid diverse viewpoints has been a hallmark of American democracy and the reason it has worked. But something has changed. Historically, healthcare policy has been one topic on which there has been broad bipartisan support. The Medicare and Medicaid Act (1965) is a classic example of bipartisan healthcare legislation. But when congress passed the Affordable Care Act in 2010, not a single Republican voted for it and not a single Democrat voted against it.

Over the last 45 years, tribalism has become ingrained in our political discourse. John Dingell (D-MI), who served in congresses for 60 years, noted that when he began serving in the House in 1955, members saw themselves first as representatives of their state, second as representatives of an institution like the House or Senate, and only third as members of a party. By the time he left Congress in 2015, the order has reversed.

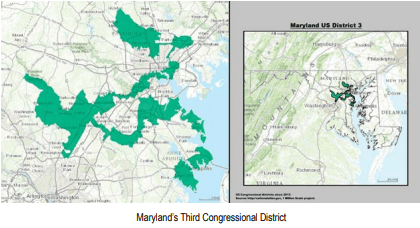

The way state legislatures draw congressional districts illustrates the extent to which parties in power will go to maintain control. One bizarre example is Maryland’s third congressional district, in which I lived until I was 16. It is called by many the most gerrymandered district in the country.

This practice has had toxic downstream effects. It amplifies the voices of those on the political extremes. Candidates in reliable liberal or conservative districts know that elections are won and lost not in the general election but in the primaries. And to win in the primaries they must “play to the base.”

We come by this honestly. We are, after all, a group-based species. But the resulting tribalism pits in-groups against out-groups, where the respective in-groups wield the political issues of the day to define and secure their status. We divide ourselves up as friends and enemies, creating hostility and polarization.

The cleavage that exists between the two tribes no longer cuts across a variety of social and cultural strata as it did 50 years ago. It’s singular and primal, so much so that a 2019 study showed that a significant number of people in each party consider people in the opposing party “evil” and that the country would be better off if members of the opposing party simply died.

The result is two Americas. At their extremes, one tribe would do away with guns altogether while the other would argue that citizens who so desire should be able to arm themselves with an M1A2 Abrams tank (version three, of course, because it’s the best). One tribe argues that abortion should be permissible to the point of birth while the other would criminalize all abortions. When either one of these Americas- right or left- senses they are losing control, they tend to dig in, inconsistencies and cognitive dissonance be damned. Both Americas defend their tribe even when it makes no logical sense to do so and (depending on the tribe) consider adherence to behavioral codes or resistance against them a moral virtue.

To circumvent this impasse, I believe we must cultivate the middle majority, by which I mean the middle 70 percent. I submit that liberal and conservative leaning people who live on either end of that middle 70 percent often have more in common with one another than they do with the extremes of their respective tribes. We must engage those with whom we disagree not on Twitter or in partisan echo chambers but in a non-partisan forum in which all viewpoints may be seriously considered, including those we find objectionable. Perhaps in such a forum we can entertain the possibility that someone who disagrees with us is not evil and does not harbor ill intent. In such a place, hospitality can be both extended and received, a place where the focus is on what unites us, not what devices us.

This may reveal some significant differences in opinion that make us uncomfortable or create uncertainty and ambiguity, but we are strong enough to manage that. To paraphrase Friedrich Nietzsche, what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, and listening to each other with open minds certainly won’t kills us. We must find the intestinal fortitude to endure the discomfort and consider the possibility that those with whom we disagree may have a valid point; they may teach us something we need to know. Listen more, talk less, or as my wife’s license plate holder puts it, “Wag more, bark less.” When it comes to hospitality, people should be more like dogs.

One thing I’ve learned in my practice is that arguing with a patient who refuses to do what I think is in their best interest never convinces them to change their mind, but if I engage them, if I meet them where they are- not as an enemy but as a friend- if I listen to their concerns and their fears and share with them why I think it would be in their best interest to do something, they may take down the walls and adopt the healthier choice. When that happens, I know that it is not because I have made a convincing argument but because I have treated them with respect, listened to their concerns, and built a trusting relationship.

We must seize the opportunity to move from hostility to hospitality, which means engaging the stranger- and those with “stranger” ideas- not as an enemy but as a friend, a guest, a fellow traveler. We must be able to see those with whom we disagree with new eyes and hear them with new ears, and recognize in all of them that we are member of the same tribe.

Catholic priest and author Henri Nouwen put it this way:

Hospitality is not to change people, but to offer them space where change can take place. It is not to bring men and women over to our side, but to offer freedom not disturbed by dividing lines. It is not to lead our neighbor into a corner where there are no alternatives left, but to open a wide spectrum of options for choice and commitment.

I would like to see TCMS, and the Tarrant County Physician, in particular, utilized by our members as such a space in healthcare. Maybe then we will rediscover- or perhaps learn for the first time- that we have much in common, that what unites us is stronger than what divides us. Maybe then we will make the stranger a guest, if not a friend.

References:

- “Hospes or Hostis.”Accessed May 27, 2023. https://biblonia.com/2020/08/13/hospes-or-hostis/

- Seib, Gerald. “Gerrymandering Puts Partisanship in Overdrive; Can California Slow it?” Wall Street Journal. November 29, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/gerrymandering-puts-partisanship-in-overdrive-can-california-reverse-it-11638198550

- Edsall, Thomas B. “No Hate Left Behind: Lethal partisanship is taking us into dangerous territory.” New York Times. March 13, 2019. https://ww.newyorktimes.com/2019/03/13/opinion/hate-politics.html

- Kalmoe, Nathan and Lillian Mason. “Lethal Mass Partisanship: Prevalence, Correlates, & Electoral Contingencies.” Prepared for presentation at the January 2019 NCAPSA American Politics: 17, https://www.dannyhayes.org/uploads/6/9/8/5/69858539/kalmoe___mason_ncapsa_2019_-_lethal_partisanship_-_final_lmedit.pdf

- Nouwen, H. “Reaching Out: The Three Movements of the Spiritual Life.” Penguin Books. 1986