Project Access and Social Determinants of Health

By Kathryn Keaton

IN 1885, ELEVEN YOUNG NUNS WITH LITTLE TO NO medical experience arrived in “bawdy” Fort Worth via horse-drawn carriage. Their charge was to staff the Missouri Pacific Infirmary. While their initial task was to tend to injured and ill railroad workers, by 1889, The Incarnate Word Order had purchased land and built a hospital that became known as St. Joseph Infirmary.1 In 1923, after a boy died from lack of medical treatment at a different local hospital, Mother Superior proclaimed that both those with means and without would have equal treatment at St. Joseph – including Black patients – when many other hospitals did not.2 During the Depression, Fort Worthians lined up for food distributed by the nuns. Renamed St. Joseph Hospital in 1966, the sisters continued staffing St. Joseph Hospital, working alongside Fort Worthʼs physicians, many of whom still have core memories of the sisters and the care provided until its closure in 2004.3

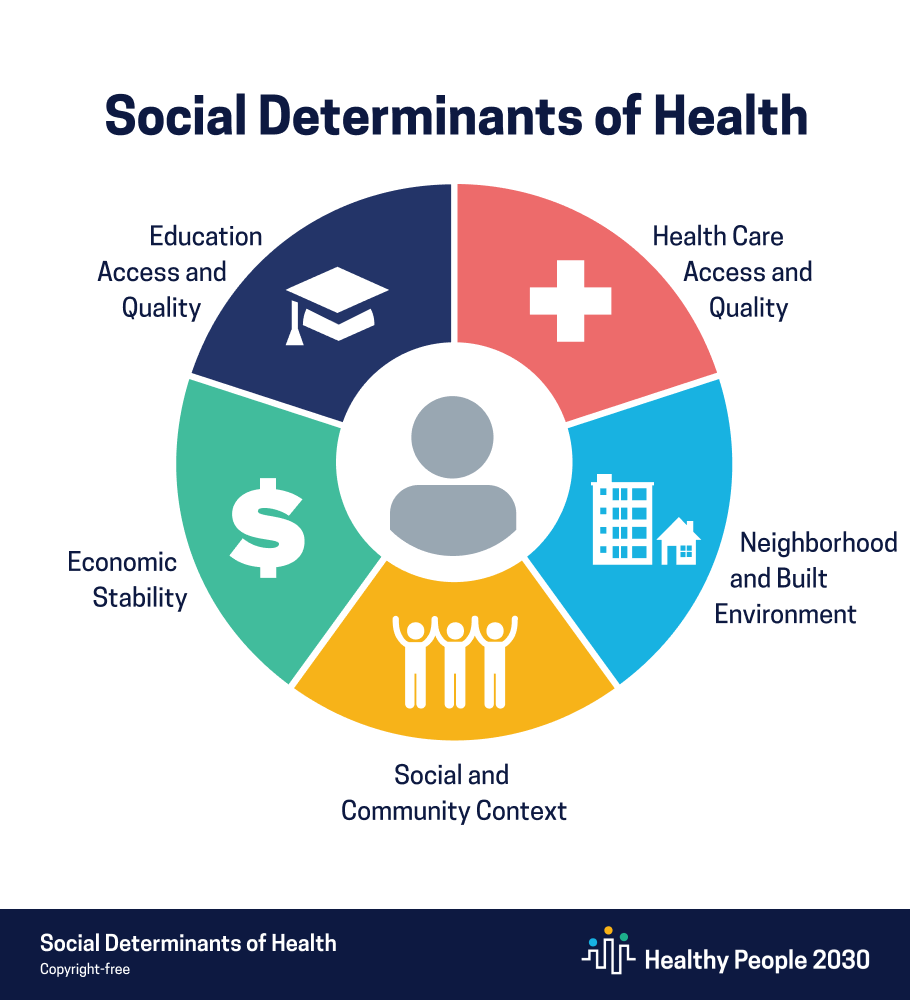

These sisters never heard the term “Social Determinants of Health,” but in Fort Worth, the nuns were pioneers of the practice. The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion defines Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) as “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality of-life outcomes and risks.”4 The World Health Organizationʼs more simple definition is “non-medical factors that influence health outcomes.”5 These issues vary greatly and are different for every community and individual,

but they each fall into one of five categories: economic stability, education access and quality, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and environment, and social and community context.6

There is no one list of what these categories include, but the factors account for 50 to 70 percent of all health outcomes.7 The Nova Institute for Health of People Places and Planet claims that “A personʼs health . . . is determined far more by their zip code than by genetics or their family history.”8 This fact is sobering considering that Fort Worthʼs 76104, home of the Hospital District,

has the lowest life expectancy in the state, first reported by UT Southwestern in 2019.9

Equitable access to timely healthcare is certainly among the SDOH that Project Access Tarrant County addresses, but since the beginning, PATC has striven to go much deeper than only access to specialty and surgical care.

The two factors most impacting SDOH for many low-income, uninsured Tarrant County patients are healthcare access and financial stability. These are inextricably linked, particularly for noncitizens who rely on their health to maintain employment and upon their continued employment for their health. Even among American citizens, the uninsured percentage of the Tarrant County (and all of Texas) population is 20 percent, double the national average; however, the percentage among Tarrant County Hispanics or Latinos is over 28.10

Healthcare access, the primary SDOH that PATC addresses, has a direct link to financial stability, especially when our intervention leads to continued or regained employment. In addition, PATC strives to identify other social determinants our patients face and address and/or refer to the best of our ability.

Primary Care

In addition to the growing number of JPS neighborhood clinics, Tarrant County is home to a vital network of free, low-cost, or sliding scale clinics that provide essential primary care to the underinsured or uninsured population. These clinics are geographically scattered across the county, including locations in Fort Worth, Arlington, Mansfield, Grapevine, Crowley, and others. Most of these are community- or church-based clinics, but Tarrant County is also home to one federally qualified health clinic (with three locations) and an optometry clinic that is based on a sliding scale model but also takes private insurance.

While most PATC referrals come from these clinics (including JPS), we also receive referrals from our volunteer physicians, emergency departments, and

the general public. The patients that come from places other than a primary care setting are more likely to have untreated (and sometimes undiagnosed) medical conditions. At least 28 percent of all active and pending PATC patients have diabetes and/or hypertension. Among Tarrant County Hispanics and Latinos, who comprise about 90 percent of all PATC patients, heart disease is the second leading cause of death, followed by diabetes at number six. In 2020, 30 percent of adults whose annual income was below $50,000 had not had a routine check-up in the past year. Because they lack basic primary care, they may not understand the importance of preventative medical care, or they may have other SDOH barriers. Others are simply unaware of what resources are

available to them.

“Ray” recently met with PATC Case Manager Karla Aguilar. Referred by a PATC volunteer ophthalmologist who specializes in retina diseases, Ray has severe diabetic retinopathy requiring surgery. He told Karla he could barely see to work and relied on his wife to drive him everywhere. While simultaneously working on the paperwork needed for Rayʼs enrollment and surgery, Karla asked about the primary care Ray has been receiving. The answer was “none.” She helped him choose from PATCʼs partner clinics and made a direct referral. She seized the opportunity to educate him on the importance of primary care,

especially with a chronic disease like diabetes. Ray seemed unaware that untreated diabetes can lead to serious health conditions, including a recurrence of his retina disease. Further into the discussion, Karla discovered that Rayʼs wife and their children, ages 12 and seven, were also without a primary care home. PATC referred the patientʼs wife to the same clinic as Ray and, since their children are citizens, referred them to a social service agency that can help them apply for Medicaid.

Healthcare Literacy

Ray needed a primary care physician, but the underlying problem was not understanding its importance. Formal education isnʼt the only factor in understanding oneʼs own healthcare. Language, culture, and knowledge of resources also impact this SDOH. PATC caseworkers frequently educate patients on what many would consider common knowledge. They also empower patients to ask questions and understand their own health.

“Sandra” called former PATC Case Manager Diana Bonilla to complain about her PATC volunteer physician. “Heʼs not treating me correctly,” she vented. “I want a different doctor.” After some investigating, Diana learned that the patient was not asking any questions of the doctor (who, of note, is very well known in his field) – and the patient admitted that she felt that, as a charity patient, she did not have the “right” to ask questions about her own health. After a long conversation, Diana encouraged the patient to take written notes of what she didnʼt understand about her care and questions she had about her condition. After Sandraʼs next appointment with the same doctor, she called Diana back. She excitedly told Diana that her questions were patiently answered, she understood her diagnosis and the prescribed course of treatment, and she was thrilled to complete her care with this same physician. Healthcare literacy and patient empowerment likely prevented a patient from discontinuing her medical care. In this case, a delay of care would have had a devastating impact on her health and her familyʼs wellbeing.

Another PATC patient, “Enrique,” was enrolled in PATC for heart issues, but he also had a severe psychiatric diagnosis. His mother was his caregiver. She was often sad about her sonʼs mental health diagnoses, and, apparently as a coping mechanism, she told Diana that she had started sampling her sonʼs medication. “I want to see how it makes him feel.” Taking a deep breath (and quickly Googling), Diana explained to her that not only would his medication

not make her “feel” the same way as it made Enrique feel but was also very dangerous. She read off a list of possible outcomes of taking a medication that was not prescribed to her by her doctor.

PATC also provides practical solutions to common SDOH, such as interpretation and transportation barriers. The 2022 Tarrant County Public Health Community Health Assessment reports that almost 6 percent of all Tarrant households have limited English proficiency; however, among Spanish-speaking households, that number is over 20 percent. Many non-English-speaking patients have adult family or friends they prefer to take with them for interpretation, but PATC has provided interpreters for close to one thousand medical appointments. Spanish is the main language requested, but we have also received referrals for patients who speak Arabic, Burundi, Farsi, French, Hindi, Korean, Mandarin, Mandigo, Nepalese, Persian, Portuguese, Swahili, Tanghulu, Urdu, Vietnamese, and Wolof. We provide in-person interpreters whenever possible; however, for some less common languages, we employ a national phone-based service.

Transportation is another potential barrier to care, especially in Tarrant County, where most municipalities have no public transit. While Arlington does have a rideshare program, it is the largest city in the United States with no public transportation. The cities that do have mass transit are limited and they usually donʼt cross city lines. Fortunately, most PATC patients have access to transportation. PATC can provide private rides for the ones who do not.

Vulnerable Communities

Immigrants and people of color are among the most vulnerable communities in Tarrant County. Because the Tarrant County Commissionerʼs Court disallows

undocumented individuals from enrolling in JPS Connection,11 the countyʼs indigent program, existing SDOH barriers are exacerbated. PATC excludes those

enrolled in JPS Connection 11, so most of our patients are the undocumented, a segment PATC has dubbed the “never served” when it comes to specialty and surgical healthcare. Eighty-five percent of PATC patients are Hispanic who speak Spanish only. The remaining 15 percent are mostly undocumented patients of non-Hispanic origin. Covering racial inequality in the United States down to our own community would take years of Tarrant County Physician magazines, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundationʼs report “What Can the Health Care Sector Do to Advance Health Equity?” gives an in-depth summary of the problems and roads to solutions for some of the factors.

One of the guiding principles of this report states,

Pursuing health equity entails striving to improve everyone’s health while focusing particularly on those with worse health and fewer resources to improve their health. Equity is not the same as equality; those with the greatest needs and least resources require more, not equal, effort and resources to equalize opportunities.12

Conclusion

Project Access excels at providing medical treatment, and this is, of course, why the program was created. We also enjoy showcasing the medical care provided. What we have not done as well is communicate the depth of services we offer to make sure that our patients not only have access to medical services, but that we also address the issues that have prevented the care in the first place. We are not a wide program, but we are deep. PATC will never be able to fix the global issues of inequality, poverty, and education; but we can (and do) address the issues facing our individual patients that impact their access to and understanding of their own care. Hopefully, they will possess more knowledge and tools for the next time they face a healthcare crisis.

References:

- Steve Martin, “Goodbye St. Joseph Hospital.” Tarrant County Physician, 90, no. 8 (August 2012): 8-9, 16.

- Regrettably, Black patients were confined to the St. Joseph basement, as were Black physicians. Riley Ransom, Sr., MD, opened the 20-bed Booker T. Washington Hospital, later known as the Fort Worth Negro Hospital and then the Ethel Ransom Memorial Hospital, in 1914. “1115 E. Terrell Ave: Tarrant County Black Historical & Genealogical Society,” TCBHGS, accessed March 2024, https://www.tarrantcountyblackhistory.org/1115-e-terrell-ave#:~:text=Booker%20T.,by%20the%20American%20 Medical%20Association.

- Texas State Historical Association, “St. Joseph Hospital,” Texas State Historical Association, accessed March 2024, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/st-joseph-hospital.

- “Social Determinants of Health,” Social Determinants of Health – Healthy People 2030, accessed March 2024, https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority areas/social-determinants-health.

- “Social Determinants of Health,” World Health Organization, accessed March 2024, https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of health#tab=tab_1.

- “Social Determinants of Health,” Social Determinants of Health – Healthy People 2030, accessed March 2024, https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health.

- Karen Hacker et al., “Social Determinants of Health—an Approach Taken at CDC,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 28, no. 6 (September 8, 2022): 589–94, https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000001626.

- “Social Determinants,” Nova Institute for Health, April 14,2022, https://novainstituteforhealth.org/focus-areas/social-determinants/.

- “New Interactive Map First to Show Life Expectancy of Texans by ZIP Code, Race, and Gender,” UT Southwestern Medical Center, accessed March 2024, https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/newsroom/articles/year-2019/life-expectancy-texas-zipcode.html.

- “Tarrant, Texas,” County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, accessed March 2024, https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/texas/tarrant?year=2024.

- Alexis Allison, “Want a Say in How JPS Operates? Hereʼs How to Get Involved,” Fort Worth Report, February 18, 2023, https://fortworthreport.org/2023/02/18/want-a-say-in-how-jps-operates heres-how-to-get-involved/.

- “What Can the Health Care Sector Do to Advance Health Equity?” RWJF, accessed March 2024, https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2019/11/what-can-the-health-care-sector-do-to-advance-health-equity.html