By Joey Berlin

Published by the Texas Medical Association for the January 2022 issue of Texas Medicine. Read the original article here.

He has relatives in medicine, so Dr. Widmer’s parents knew what sham lawsuits and their ripple effects were doing to the state’s physician community, and they did their part to help.

“We were the only house on the street with a ‘4’ sign,” Dr. Widmer recalled. “I remember that to this day.”

Now that he’s at the helm of TEXPAC, the Texas Medical Association’s political arm, Dr. Widmer urges his TMA colleagues to join the effort to unify medicine’s voice in politics.

TEXPAC leaders say victories like HB 4 happen because of grassroots, physician-driven efforts to elect friends of medicine to office. The same goes for more recent major victories like the new law that allows physicians to earn exemptions from insurers’ prior authorization requirements, or the overwhelmingly successful stands against nonphysicians’ attempts to practice medicine.

TEXPAC helps generate those victories with a dogged, systematic evaluation of candidates who have the profession’s best interests at heart, endorsing and funding the ones who demonstrate their medical mettle. It’s the Party of Medicine, not of Democrats or Republicans; a candidate’s stances on TMA’s top issues, and the impressions of TEXPAC physicians in a candidate’s district, are what carry the most sway.

Even in what he describes as a caustic modern political landscape, Dr. Widmer says staying on the sidelines isn’t an option, with medicine under attack from every direction.

“No longer can we afford as physicians to have the mentality that, ‘I’m just gonna go to my office, practice, and [then] go home.’ There’s too much at stake,” he said. “There are too many people trying to do what we have gone to school and trained years to do. We have to stand up for that, and we have to get active and get involved.”

Members’ role

The annual financial contribution required of a TEXPAC member – while an important piece of the puzzle – is just one aspect of what the organization needs from its participants, says TEXPAC Executive Director Christine Mojezati.

Physicians who join TEXPAC have the flexibility to make their membership as involved as they want or are able. That can just mean paying your dues, but TEXPAC asks its doctors to do more to fully help medicine’s cause. Some of the most important activities a TEXPAC member can engage in are:

• Participating in your county medical society, including taking part in its legislative committee and/or candidate evaluation process.

• Getting to know the legislators in your district or area, such as by visiting them in their local office, calling them for a conversation, or taking them to coffee or lunch. Doing so gives physicians a chance to relate stories about their practice and how certain policies are affecting their day-to-day life and their patients.

• Responding to TMA Action Alerts, which mobilize members to contact lawmakers on particular issues or legislation of urgent importance.

“Financial contributions not only gain us access but also give us a seat at the table,” Ms. Mojezati said. “But there’s nothing like the personal stories of a physician about how they cared for their patient, or why a certain bill or law would affect how they would care for their patient.”

An entry point to getting acquainted with your local elected officials is participating in TMA’s monthly First Tuesdays at the Capitol lobbying events during regular sessions of the Texas Legislature, says Fort Worth allergist-immunologist Robert Rogers, MD, a past chair of TEXPAC. First Tuesdays – which went virtual in 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic – allows physicians face time with legislators, an avenue for cultivating the relationships that lead to receptive ears.

“It is really meaningful for our elected representatives and senators to actually know us – to be able to recognize you by name when they see you in the Capitol or in their local office,” Dr. Rogers said. “That doesn’t mean we always get everything we want. But it’s much easier to have a discussion about issues with the people that you’ve already developed a relationship with.”

Those conversations – and other vital TEXPAC activities – aren’t merely confined to the four-plus months when the legislature meets every odd-numbered year. In fact, much of the work comes during the interim period between sessions, when TEXPAC makes itself available as a resource both to legislators and to candidates running in even-numbered years. The interim, Ms. Mojezati explains, is when legislation is written, refined, and prefiled, and when there’s time for stakeholder meetings.

“TEXPAC provides all the background information that any of us would need to be able to go in and discuss issues that are important” in conversations with lawmakers, Dr. Rogers added. “It’s really helpful to do that during the interim, because [lawmakers] have a lot more time to meet with us and discuss things.”

Finding medicine’s friends

If one impediment to joining TEXPAC is believing that your voice won’t be heard in an organization of thousands of members, think again.

In evaluating candidates for an endorsement, TEXPAC’s focus is highly localized, says Sara Austin, MD, an Austin neurologist and chair of TEXPAC’s Candidate Evaluation Committee. That means when you provide input on whom medicine should support in your district, you and your community colleagues won’t be drowned out by thousands of others hundreds of miles away.

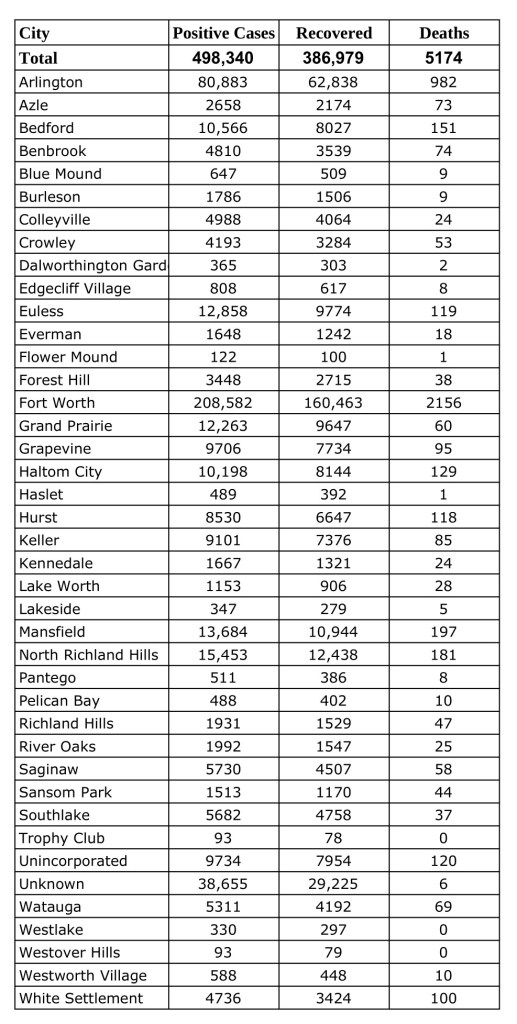

For incumbents running to keep their seat, eligibility for TEXPAC endorsement comes down to meeting two criteria: an objective analysis of their voting record and a subjective score based on the candidates’ meetings and interactions with local physicians, both TEXPAC members and nonmember physicians. (See “TEXPAC’s Endorsement Process,” this page.)

TEXPAC evaluates candidates on a point system based on how they voted on key bills most important to medicine’s agenda: Voting with medicine on a particular bill is worth one point; not doing so is worth zero. Candidates lose points if they filed or signed onto an antimedicine measure, such as a bill that would dangerously expand other practitioners’ scope of practice or seeking to raise the medical liability damages cap. An 80% score on that point system allows for a possible endorsement.

The subjective portion consists of physicians – with the help of detailed TEXPAC candidate briefing documents – interacting with candidates and grading them on a scale of one to five, the higher the better. Averaging a score of three is required for consideration for an endorsement.

The “80 and three” rule is a weed-out process for incumbents. Candidates who pass both of those tests and earn local physicians’ recommendation for an endorsement must then pass muster with the Candidate Evaluation Committee, which sends its recommendations to the full TEXPAC board for approval.

For new candidates with no voting record to evaluate, the interviews and interactions with local physicians and county medical societies largely determine which aspiring officeholders make it to the Candidate Evaluation Committee. Incumbents also need to prove they’re willing to sit down and listen to their district’s doctors.

“There are some incumbents who never vote with the House of Medicine, so we definitely don’t endorse those people,” Dr. Austin said. “[We also] try to find out from the local physicians if that [legislator] was available or accessible [to meet]. That’s important.”

For state Sen. Charles Schwertner, MD (R-Georgetown), TEXPAC was “instrumental in helping me understand the lay of the land” when he first ran for a House of Representatives seat in 2010 as a “very green” candidate. TEXPAC also was instrumental in helping him obtain early financing and in fundraising efforts. He launched his run with local support from the Williamson County Medical Society.

“That’s what TEXPAC is all about: making sure that the individuals that are friends of medicine have the amount of resources necessary to get their campaign message out, and then hopefully win election and be able to serve,” Senator Schwertner said.

TEXPAC endorsements also involve a degree of pragmatism, Dr. Rogers adds. In addition to a candidate’s promedicine stance, the Party of Medicine considers his or her likelihood to win.

“We have a couple of major objectives in the candidate process. One is to try to help elect people that are naturally inclined to support what we do, if there’s a competitive race,” he said. “We also know that there are a lot of races that are not competitive at all, and who’s going to get elected is very clear. And we need to have influence with people that are actually going to be in the building making decisions. That means that we might endorse the candidate that isn’t apparently very helpful to TMA, but that really could be helpful on a specific issue.”

Sometimes, Dr. Rogers added, one helpful vote on one specific bill “can happen from somebody that isn’t a natural friend.”

If you’re a TEXPAC member whose candidate did not earn endorsement, the organization’s Physicians For program offers another way to support your preferred candidate by connecting TEXPAC doctors with other physicians in their House or Senate district to rally around their preferred candidate.

The program “has proven to be very successful,” said Ms. Mojezati, TEXPAC’s executive director. “Not only has it helped candidates be victorious in races but it also helps because [in] any situation where TEXPAC either did not endorse them or didn’t make any endorsement, we now have physician relationships with that candidate. We never want to not have friends in the Capitol.”

TEXPAC has maintained success rates of 95% or greater with its endorsements during recent election cycles. For instance, during the 2020 state primary elections and a handful of ensuing runoffs – which usually involve most of Texas’ most competitive races – TEXPAC made more than 130 endorsements, and 98% of those candidates won and moved on to the general election. In the November 2020 general election, 97% of TEXPAC-endorsed candidates won their sought office.

Overcoming apathy

TEXPAC acknowledges physicians’ reluctance to get involved in politics: “It’s a highly charged arena right now,” notes Dr. Widmer, TEXPAC’s chair.

And there’s a level of apathy, Dr. Rogers adds; physicians just want to do their jobs.

But much progress has happened on TEXPAC’s watch, from tort reform in 2003 to the 2021 legislation allowing physicians to earn a “gold card” out of the prior authorization process.

Back during the days of tort reform, long before jumping into politics, Senator Schwertner was a young physician taking part in the first-ever First Tuesdays in 2003. HB 4’s success that year was the product of a unified approach between physicians and business interests, and that unity and having “as many allies to the House of Medicine” as possible are key to legislative success, he said.

More recently, he noted, TEXPAC has been vital in bolstering TMA’s fight against scope-of-practice bills and “the onerous profitmaking and tactics of insurance companies,” such as narrow networks.

“Medicine is a highly regulated, government-controlled, and actually government-funded profession. As such, it is vital to those individuals from just a … professional standpoint to be involved,” Senator Schwertner said. “If you’re not being an active participant, and voting and helping choose candidates … that share your ideals, then someone else is doing it for you. And you’re going to live under the laws that those other individuals pass.”

Casting aside the repulsion of modern red-versus-blue politics – and doing what’s best for patients and the practice of medicine – is important to medicine’s success, Dr. Widmer adds.

“If we keep that as the focus of what we’re doing with TEXPAC, then we will be stronger for it. We will have a more cohesive, hopefully larger body, and we’ll be able to make a bigger impact.”